|

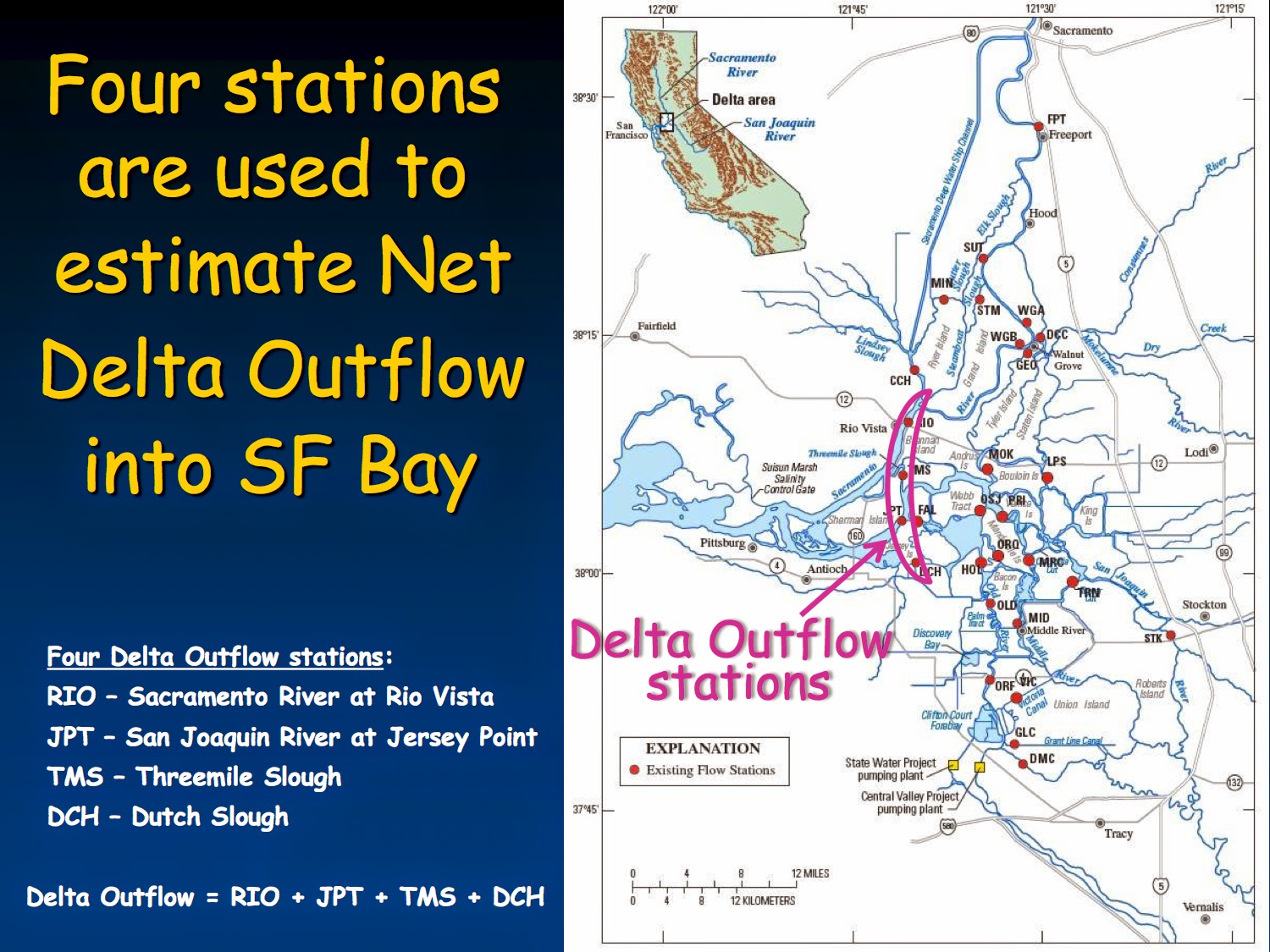

| USGS acoustic Doppler devices near Rio Vista bridge keep track of fresh water outflow from Delta channels |

Small Differences Matter During Drought

Suits Aims to Stop Transfers

|

| Biostatistician Thomas Cannon challenges State outflow estimates in environmental suit. |

Hoping to stop water transfers of 175,000 acre feet, approved by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation this spring, two environmental organizations have filed suit in federal court. They requested an expedited hearing to halt the transfers that are scheduled to begin this month. Plaintiffs charge that the Bureau did not do a proper environmental analysis before approving the transfers, and the flow monitors maintained by the USGS in the Delta are poised to play a staring role in the case.

|

| USGS technician repairs an outflow monitor at Three-Mile Slough in June. |

If the outflow is truly as low as the USGS monitors indicate, it means that salt water is constantly threatening to move up the estuary and that a number of fish species, including the iconic longfin and delta smelt, are at risk of being carried into the export pumps which carry water to the south of the State.

Accuracy of USGS Monitors Challenged

Science panel Validates New Outflow Estimates

The same disparity that was evident in 2013 showed up again this year. NDOI estimates were way higher than outflow as measured by USGS monitors. Whereas California officials believe outflow in the Delta is around 4,000 cfs this summer, the actual figure measured where the Delta meets the Bay is about zero. In light of these findings, the State Water Board will be looking at "possible changes in determining outflow," said SWRCB engineer Rick Satkowski.

Delta Smelt Not in Normal Habitat

|

| Four USGS stations monitor outflow where Delta water enters the Bay; official outflow monitors are located further upstream toward Sacramento and where rivers enter the Delta. |

Northern Communities also at Risk

Salt Levels Due to Affect Pumps

CALIFORNIA'S WATER STORAGE CRISIS: THE BATTLE AT TEMPERANCE FLAT

|

| Banner Peak and Thousand Island Lakes mark the headwaters of the San Joaquin River in the Ansel Adams Wilderness. Photo by Alex Breitler |

A Year Like No Other

A Dam You Love or Hate

|

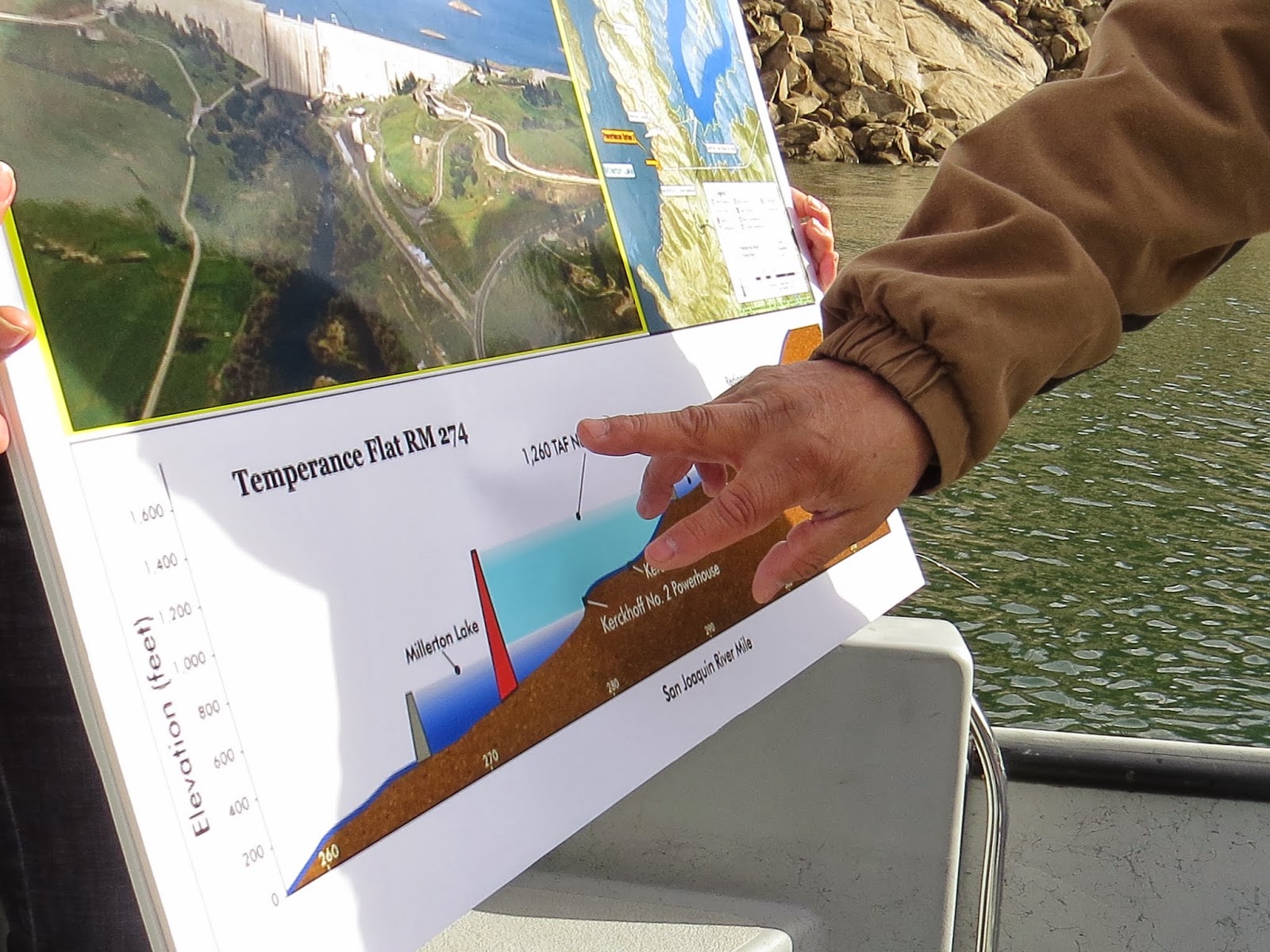

| The proposed dam at Temperance Flat (red) would hold 1.2 million acre feet of water, extending another 16 miles up the river behind the current Friant dam (in gray and pictured at top) |

Temperance Flat is one of the most controversial storage projects in California. Farmers want it; environmentalists oppose it; Federal officials have left it on the shelf for years. But this year, in the wake of California's epic drought year, the project is alive and well. Like nothing else, these months with no precipitation have driven home the awareness that California does not have enough water in storage to get through really bad dry periods.

Bright Dream; Original Sin

|

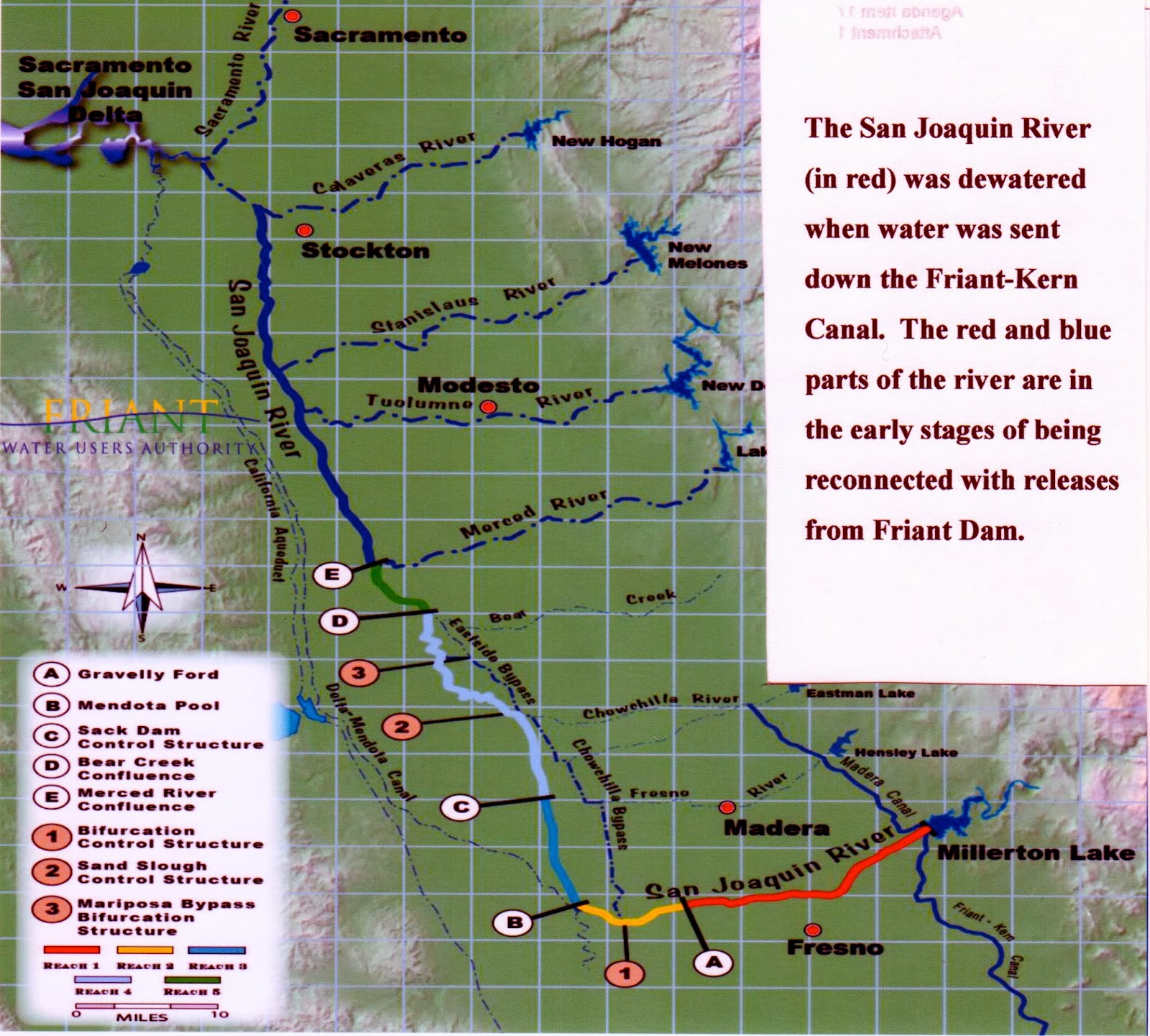

| The Federal Central Valley Project in Fresno created two separate rivers. |

In laying the concrete for this farming miracle, engineers completely reversed the flow of the San Joaquin River. They sent its waters moving south to Kern County instead of north to the Delta. The river that inspired John Muir disappeared within months. Salmon runs abruptly ended. Landowners along the course of the northern-bound river lost their water, among other deleterious effects.

An Historic Win for the Ecology

|

| A stretch of the once magnificent San Joaquin River, has been dry for 70 years. With restoration releases, it shows a meager stream of new water. Bureau of Reclamation |

In one of the longest running legal cases of its kind, the Natural Resources Defense Council won a settlement seven years ago that forces the Friant Authority to release enough water into the old channel to restore the river and restart the salmon run. Environmentalists don't want any more water – not even flood waters – to be held behind any dam on the San Joaquin River. Besides, they claim, farmers already take up to 95 percent of the watershed's precipitation. Do they have to have the last .05 percent? Can't they let even one drop reach the ocean?

The Case for Farmers

|

| Friant's Mario Santoyo: "I couldn't move the water." |

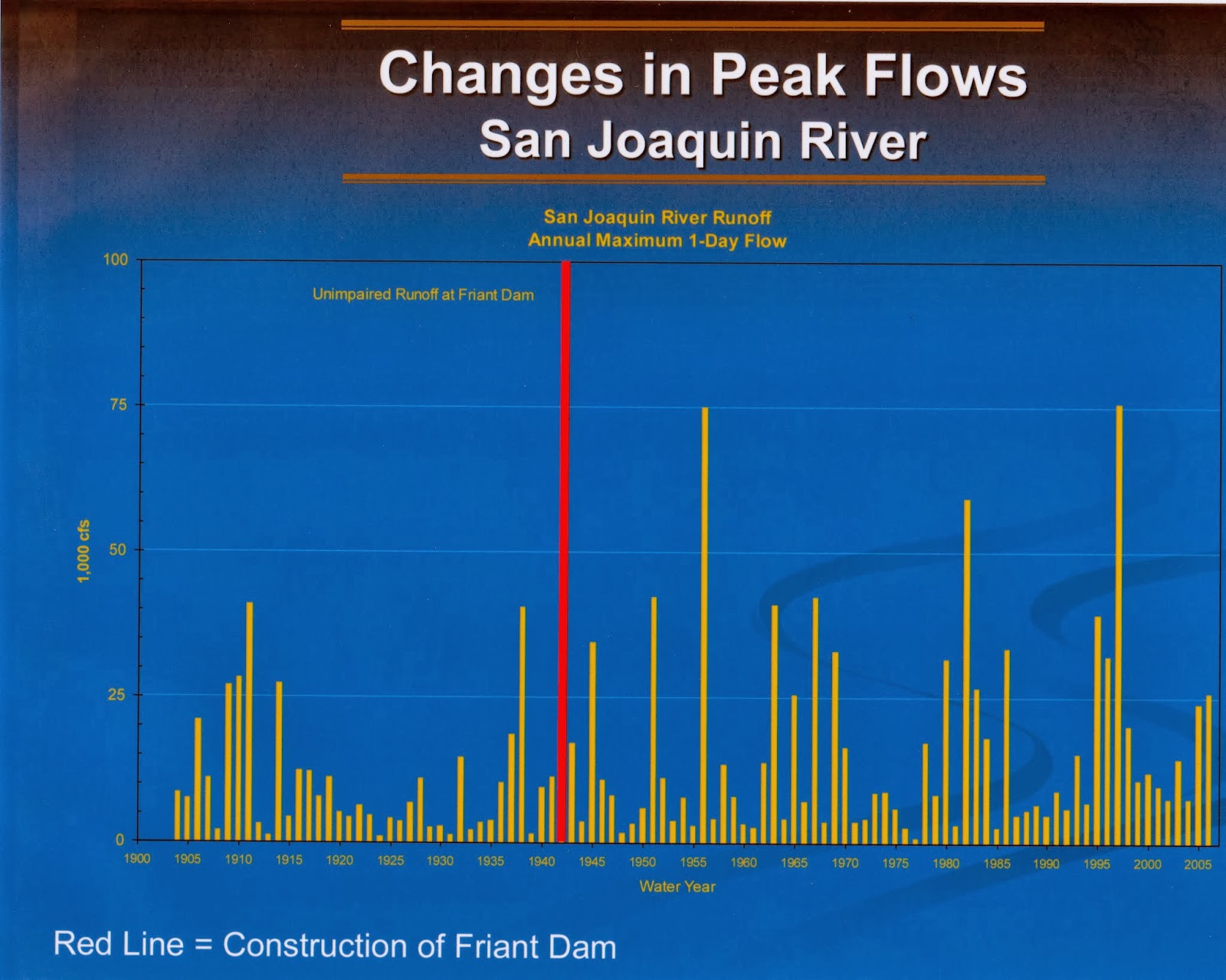

In 1997 (the year that Yosemite Valley flooded), a rain-driven cascade of water came down the San Joaquin canyons that stunned Santoyo. It came so fast and in such volume (120,000 cubic feet per second) that no mere dam could hold it, certainly not Friant. It was like a football stadium full of water plunging into the reservoir every second, he said.

A Challenged Dam in an Era of Climate Change

|

| Chart shows higher peak flows in the San Joaquin during 20th century, from 1905 to 2005. Photo from the Friant Water Authority |

Unlike other reservoirs in the central/southern Sierras, like the two million acre feet Don Pedro Lake to the north, or the one million acre feet Pine Flat reservoir to the south, Millerton holds only 500,000. It works more like a diversion basin than a reservoir, in that it channels water immediately into the Friant-Kern and Madera canals. By this means, it sends most of the water –1.8 million acre feet – that comes down the mountains onto the fields.